‘See

nowt, hear nowt, say nowt’. So went the counsel of wisdom on the eastern

fringes of Manchester

Those who grow up

where momentary inattention to the rule can be costly develop a second sense,

an involuntary safety mechanism that manages the reflexes: brows do not lift in

surprise, eyes do not betray fear or recognition. This process was well

ingrained by the time I was introduced to Belinda’s father. Ah, Belinda! Where are you out there? Somewhere comfortable, no

doubt, some better class of neighbourhood, chic and secure, which you grace

with your elegance. Or has the elegance abandoned you now, leaving you a little

bent, with rheumatic movement? Would it lift your spirits to know that in the

head of this long forgotten admirer you are still twenty-two, your heels

clicking with youthful rhythm, your smile shining with undiminished luminosity?

Forty years have passed, yet I need only to close my eyes to have you step into

my cerebrum, occupying it as of right, clearing out the trappings of two

marriages and three kids, haunting it instead with your own image: the smell,

the sight, the sounds of your younger self. Would it have been different had

your father not feared me?

I had been gone

from Newton Heath for about three years when we met, and was living in

Davyhulme, an altogether different Manchester

Had I been more

athletic, I would that night have somersaulted my way home and entered the

house via the upstairs bedroom window, reaching it with a single spring. But I

was not athletic. Instead, I floated the two-mile walk, turning unseen corners,

crossing anonymous roads. She had agreed to see me again – SHE had agreed,

laughing at my cockiness, she had AGREED. What was her name? Linda? Brenda? It

didn’t matter. What mattered was that a soft-spoken angel, a gentle, graceful

goddess had moved into my raucous world and not been repelled by its

gaucheness, its clumsy, boastful shell. She was unlike any girl I had known, in

voice, movement, in every way, and I was wildly, stupidly in love.

Belinda lived in Sale Stretford ,

about half-way between our homes, where our bus routes converged, but the

inconvenience of this arrangement soon became apparent. So, I bought a car, an

old Austin A40 that had seen better days, but it served its purpose. I was able

to drive across to Sale to collect her, take her

into Manchester

How can one build a

bridge across an ever widening gulf? Whatever the topic, my unsuspecting

goddess placed herself further beyond reach at each meeting. My efforts to

narrow the gap seem trivial now, but involved significant sacrifice at the

time. Whereas the pub had been my habitual source of entertainment it was

superseded by Belinda’s preferences; theatre, live concerts and dancing. My

adoration of Manchester United yielded to tennis, a game that I had considered

unmanly. Such matters were, at least, open to correction, but others were

historical fact. When education was mentioned Belinda’s shining at Grammar

school contrasted with my habitual truancy from a secondary modern, and in

conversation about holidays she spoke of times spent in places known to me only

through the pages of brochures. ‘Abroad’ to me was the Isle

of Man , while she had relaxed on two continents. So, I listened,

nodded knowingly, and lied.

One subject though

played a greater part than any other in heightening my awareness of the gap

between us: our parentage. Belinda’s mother was a secretary in a solicitor’s

office: mine was a cleaner in a factory canteen. Her father was a businessman

in the entertainment industry, and a musician, while my vaguely remembered dad

was a bus driver who had done a runner some years before. We pretend today in England

When the dreaded

day arrived, after a week of rehearsed greetings and abandoned excuses for

cancelling the appointment, I washed the car thoroughly in a futile effort to

make mutton look like lamb, and drove across to Sale

The hall that I

entered almost on tiptoe, as if my great feet would damage the tiled floor, was

the size of my bedroom, with three heavily panelled doors off, and a broad,

wooden staircase curling upwards. My fragrant hostess opened one of the doors

and led me into a sitting-room filled with wood and leather. No cheap, fitted

carpeting here, but a sea of glowing parquet on which floated richly coloured

rugs. ‘Take a seat Harry. I’m off to the kitchen, but Belinda will be down any

moment. Can I get you a drink?’ My stay-sober resolution – ‘for God’s sake

don’t get drunk tonight’ – dictated the polite refusal, and I seated myself

gingerly on the edge of a leather covered settee that would have looked

ridiculously ostentatious in my own home, but fitted in here. I remained thus,

leaning forward, elbows on knees, gawping at the picture festooned walls, until

Belinda put in an appearance. I

jumped to my feet, and for want of something better to say, blurted out the

question that had just come to mind ‘Hello love, where’s the ‘telly?’ She

giggled, and opened what I had presumed to be a drinks cabinet.

‘Ah, here’s daddy’.

The door from the hall had swung open to administer the greatest surprise I

ever experienced, before or since. As ‘Daddy’ approached I stared incredulously

at the monkey-like features; black button eyes, vestigial nose, and thin lips that

stretched in imitation of a smile. The simian impression was heightened by his

stoop, and awkward, swinging gait across the room due to what was commonly

called a ‘club foot’, his left, which wore a surgical boot with a six-inch

thick sole. For once, my Newton Heath street-training almost failed me, but not

quite. The laughter that bubbled within showed as no more than a smile to be

interpreted as a courtesy. ‘Hello Harry, I’m pleased to meet the young man who

has set my daughter’s tongue wagging so much.’ ‘Pleased to meet you Mr; Payne.’

The thin lips stretched further. ‘Please call me Stanley, I feel that we know

each other already.’ How true! How true mate! Or rather, I knew him, but not as

Stanley, or Mr Payne. To me, he was known as Gordon, and I knew well his music,

and his business. My face betrayed not a flicker of the relief I felt. All the

nervousness of the last few days vanished and I suddenly felt my old, cocky

self.

Much of the evening

was devoted to the predictable interrogation, most charmingly conducted by

Stella, my beloved’s mother, while Stanley Culcheth

Lane Church Street

That was the last

time I saw Belinda. A couple of letters went unanswered, and the only benefit

from a telephone call was the opportunity to hear Stella’s mellow voice. After

a few weeks I switched into my ‘not caring’ mode: I’m very good at not caring.

A brief affair with Cathy, who worked at the local dry-cleaners, led to her

first pregnancy, our marriage, and eventual parting of the ways. That was

followed by life with Janet, two more offspring, divorce, and memories for

company. Of those memories, the most intense reach back to Belinda, and her

father. It is they who rob me of sleep, causing me to ponder unanswerable

questions. Did Belinda know, or was her father fearful that she would learn?

Was the break at his instigation, or had she simply tired of my unpolished

manner? If the former, he need not have worried: my code would have protected

him from revelation. Though Belinda avoided me, I did see her father once more,

but from some distance.

Curiosity drove me

back to Church Street ,

Newton Sale

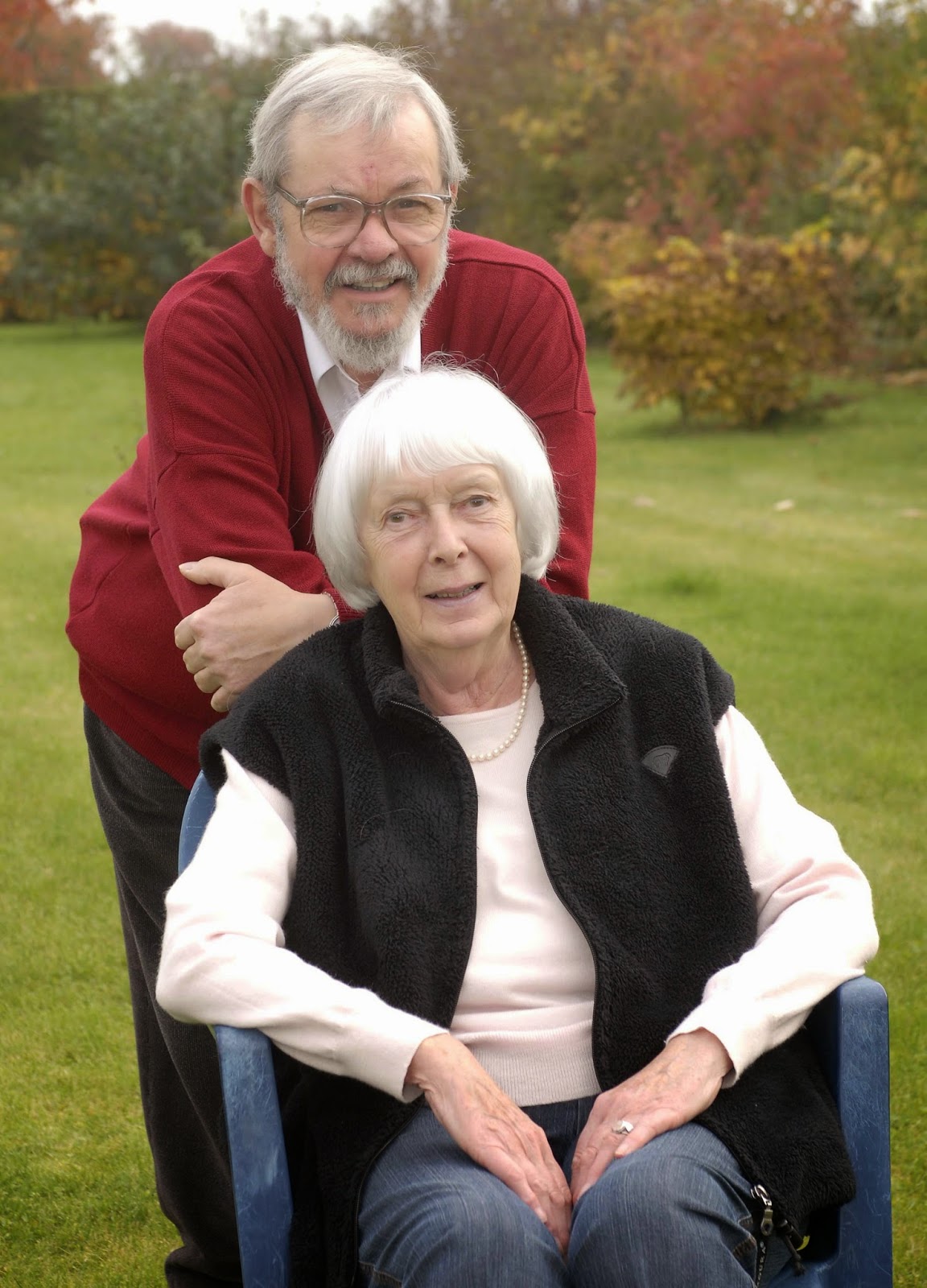

Mancunian Tom Kilcourse is an ex-miner, ex-bus driver, ex-Ruskin College & Hull University student, ex-management guru, and at 77 nearly expired. He writes for fun because he can’t make it pay. He has self-published two short-story collections, a brief autobiography, and three novels with a fourth in preparation. He retired to France in 1998 and returned with his wife last year to live in Cheshire.

No comments:

Post a Comment